Tuesday, June 18, 2024

The Golden Song Book

Monday, June 17, 2024

Making Believe: The Wizard of Oz and the American Musical

"Making believe" is, I argue, what makes The Wonderful Wizard of Oz an American fairy tale and why the genre of the musical has been popular for adapting the story. I like this concept of make-believe because it combines interior imagining with the idea of actively making or doing something--or to put it another way, performing. Participating in American musical theater is a great act of make-believe in which people perform their American identities. How appropriate, then, that the story known as "the American fairy tale" and the genre of the musical have such a close relationship, from the first Oz musical extravaganza to MGM's The Wizard of Oz, The Wiz, Wicked, and backyards and school theaters across the USA.

Read more about the Wizard, make-believe, and how The Wizard of Oz exemplifies the American musical in Oz and the Musical: Performing the American Fairy Tale.

Friday, September 2, 2022

Oz and the Musical: Performing the American Fairy Tale

Oz and the Musical: Performing the American Fairy Tale considers the special relationship between Oz and Musicals in the US. Drawing on my experiences as a fan, scholar, and practitioner I argue that musical adaptations of The Wizard of Oz make the "American fairy tale" available as participatory culture. In return, Oz contributes to the musical's pedigree as an America art form. Along the way, I discuss L. Frank Baum's The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), the popular Broadway adaptation of 1903, the famous MGM film, the stage and screen versions of The Wiz (1975 and 1978), and Wicked (2003). The book concludes with a chapter on home, school, and community musical performances of Oz. Central to these adaptive performances are the contributions of diverse American producers, performers, and audiences, including kids, immigrants, Black people, and queer people, who have expanded and transformed the American fairy tale through song, dance, and the gestures of musical theater.

Oz and the Musical: Performing the American Fairy Tale considers the special relationship between Oz and Musicals in the US. Drawing on my experiences as a fan, scholar, and practitioner I argue that musical adaptations of The Wizard of Oz make the "American fairy tale" available as participatory culture. In return, Oz contributes to the musical's pedigree as an America art form. Along the way, I discuss L. Frank Baum's The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), the popular Broadway adaptation of 1903, the famous MGM film, the stage and screen versions of The Wiz (1975 and 1978), and Wicked (2003). The book concludes with a chapter on home, school, and community musical performances of Oz. Central to these adaptive performances are the contributions of diverse American producers, performers, and audiences, including kids, immigrants, Black people, and queer people, who have expanded and transformed the American fairy tale through song, dance, and the gestures of musical theater.

"Bringing together his expertise in American musical theatre and childhood studies, Bunch walks readers through a culturally-grounded understanding of the world of Oz as found in books, on stages, on screens, in homes, and in communities. Deep scholarship and deep engagement with fan culture create a persuasive reading of the Oz fairy tale as quintessentially American, consciously performative, and full of a kind of theatrical humbug that makes the story perpetually adaptable and reflective of our changing society."

Dr. Jessica Sternfeld, Associate Professor of Music, Chapman University

"Oz and the Musical beautifully analyzes the utopian possibility of the Oz story in forging a sense of American belonging. Exploring the form of the musical and its participatory potential, Bunch embraces the value of make believe and the performative to American inclusiveness. In engaging, lively prose, he reads Oz, The Wiz, and Wicked as fabulous expressions of the variety of the American imagination."

Katharine Capshaw, Professor of English and Africana Studies Affiliate, University of Connecticut

"[Bunch's] ability to weave previous scholarship with his own fresh takes, and to intertwine Oz musicals with Oz's utopian ideals; the participatory culture of musicals; and America's darker side of exclusion, erasure, and appropriation mak Oz and the Musical a worthy addition to the bookshelves of scholars and fans alike.

Dina Schiff Massachi, The Baum Bugle

Friday, February 25, 2022

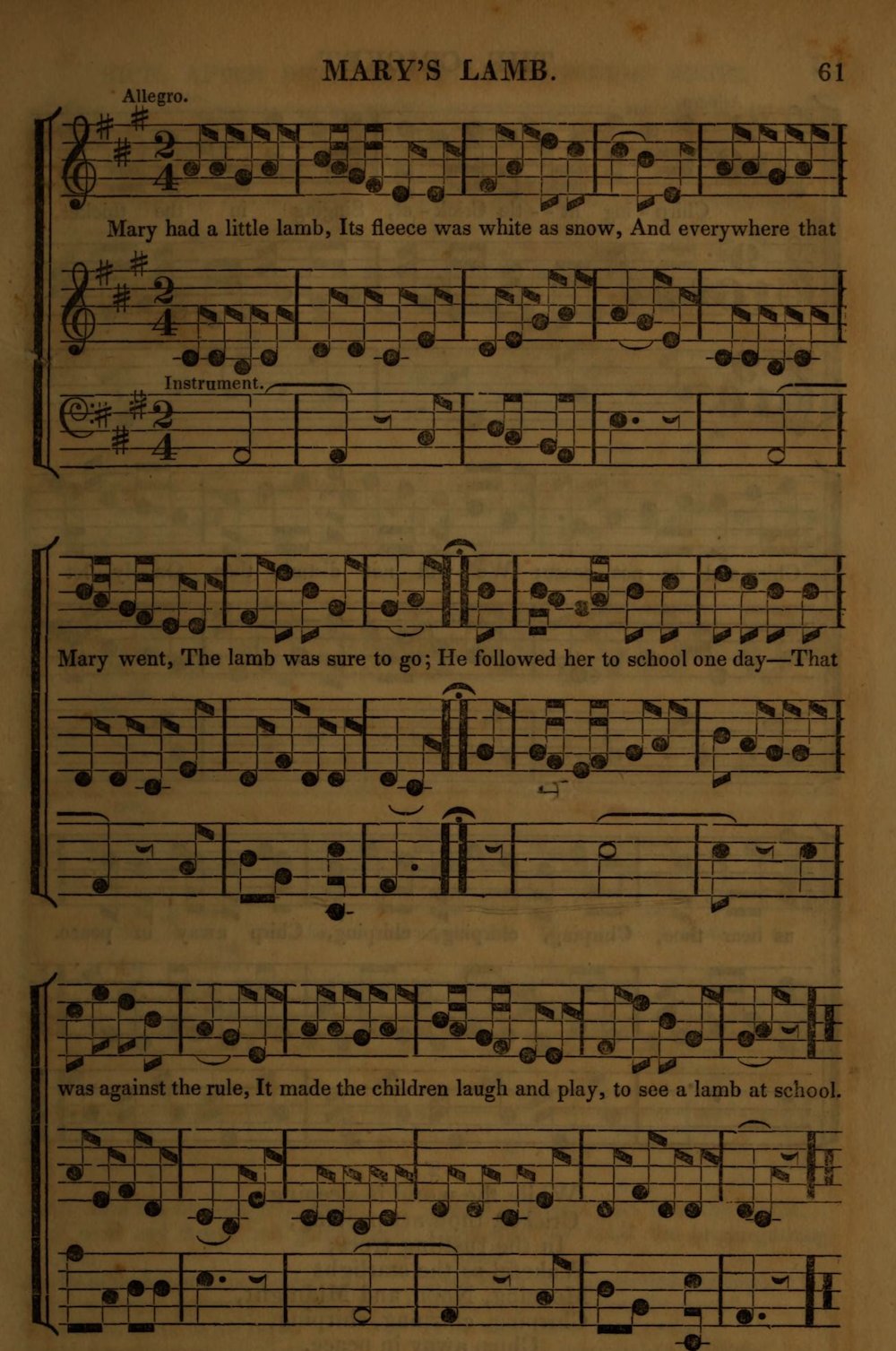

Mary Had a Little Lamb

The poem was published by Sarah Josepha Hale as part of a collection of children's verses in 1830. She had been encouraged to produce this volume by Lowell Mason, who led the founding of school music education in the United States. He was in search of material he could set to music for instruction, and he included "Mary's Lamb" in his Juvenile Lyre, Or, Hymns and Songs, Religious, Moral, and Cheerful, Set to Appropriate Music, For the Use of Primary and Common Schools. This songbook was used in Boston public schools and was probably the first such collection in the United States. Hale's verse is reportedly based on the true story of Massachusetts girl Mary Sawyer, who took her lamb to school and in whose honor the city of Sterling Massachusetts has erected a statue.

|

| "Mary's Lamb," with music by Lowell Mason from the Juvenile Lyre, 1831, |

Boston Literary History

Pound, Gomer. "Mason's Hand in "Mary's Lamb"." The Bulletin of Historical Research in Music Education 7, no. 1 (1986): 23-27. http://www.jstor.org.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/stable/40214696.

Richards Free Library

Friday, May 14, 2021

Olaf: Frozen's Child

Olaf is childhood personified. A creation of Elsa in her childhood, he rematerializes in her cathartic release in "Let it Go," embodying her interior truth and child inside. Like childhood, Olaf is immanently ephemeral, in danger of melting away. Great care is taken to preserve him in flurries and permafrost, to hold on to him like a favorite toy from one's own childhood. Kids might identify with him and derive pleasure from his humorous performance of childishness. He revels in the unruliness of childhood, constantly coming apart and rearranging. His comedic turns knowingly disrupt adult, normative logics.

Monday, April 12, 2021

The Humbug of Children's Literature

Wednesday, March 31, 2021

Barney and Friends: Let's Help Mother Goose!

Friday, March 26, 2021

Ring Around the Rosie

|

| Kate Greenaway, "Ring-a-ring-a-roses," Mother Goose (1881) |

Ring around the rosieA pocket full of posies

Upstairs, downstairs

We all fall down.

It’s a strikingly simple game. You hold hands and move in a

circle till you get to the part about falling down, and you fall down. Then you

get up and do it again. I’ve hardly ever seen any additional verses or accounts

of the game being any more complicated. You just keep repeating it for the

sheer simple pleasure of it. There's no story (it's not about the plague), and the main appeal seems to be the fun of spinning and falling (the dizzying kind of play Roger Caillois called ilinx). In some historical accounts, the last person to fall

or squat becomes the “rose tree” and stands in the center of the circle for the

next round. There’s at least one account of it being used by young children in

the US as a kissing game. I wonder if this suggests some kind of connection to

play party games that nineteenth-century adolescents played as outlets for flirtation

and courtship.

The tune currently most associated with the rhyme in the

United States is an iteration of what Patricia Sheehan Campbell has called the

children’s “ur-song,” famously sung as “nana nana boo boo!”

It first appeared in print in Kate Greenaway’s Mother Goose;

or, the Old Nursery Rhymes (1881).

Wednesday, March 24, 2021

Fisher-Price Change-a-Record Music Box

The Fisher-Price Change-a-Record Music Box was first released

in 1971. It includes 5 double-sided toy records in

different colors with a total of ten songs. These are kept in a storage

compartment in the back of the record player. Like so many musical toys, it has

a handle for portability. I'm still trying to figure out what it means for a music box to pretend to be a record player. Is this a practice record player for very young children who are not yet able or allowed to use a real one, or is it a toy in its own right with pleasures specific to its form?

Sunday, March 21, 2021

Children Are Angels

In which Donald encounters a gap between the child in the book and feathered reality of Huey, Dewey, and Louie.

Thursday, December 13, 2018

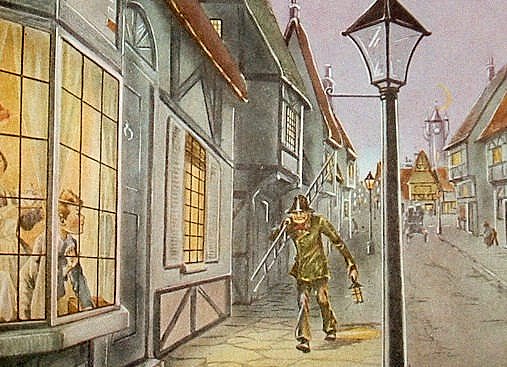

Watching for the Lamplighter in Kids' Literature

My tea is nearly ready and the sun has left the sky;

It's time to take the window to see Leerie going by;

For every night at teatime and before you take your seat,

With lantern and with ladder he comes posting up the street.

Now Tom would be a driver and Maria go to sea,

And my papa's a banker and as rich as he can be;

But I, when I am stronger and can choose what I'm to do,

O Leerie, I'll go round at night and light the lamps with you!

For we are very lucky, with a lamp before the door,Both Cummins and Stevenson describe children who take pleasure in waiting each evening to see the local lamplighter passing through on his rounds and lighting the nearest lamp. These episodes seem to suggest a common childhood experience in the pre-electric era, as well as a common trope in children's literature--that there is a special, sentimental relationship between children and working class adults.

And Leerie stops to light it as he lights so many more;

And O! before you hurry by with ladder and with light,

O Leerie, see a little child and nod to him tonight!

Tuesday, December 11, 2018

Little Women Make Theater at Home

As Marah Gubar has noted, the Christmas play-acting scene in Little Women gives us some insight into the importance of home theatricals in the nineteenth century, which, as in this scene, were created by young people for audiences that were often mostly other kids. These home theatricals had a symbiotic relationship with professional theater, prompting the production of professional children's plays, which in turn influenced private performance, and so the cycle goes.

This scene as it appeared in the 1933 film is featured here.

Monday, December 10, 2018

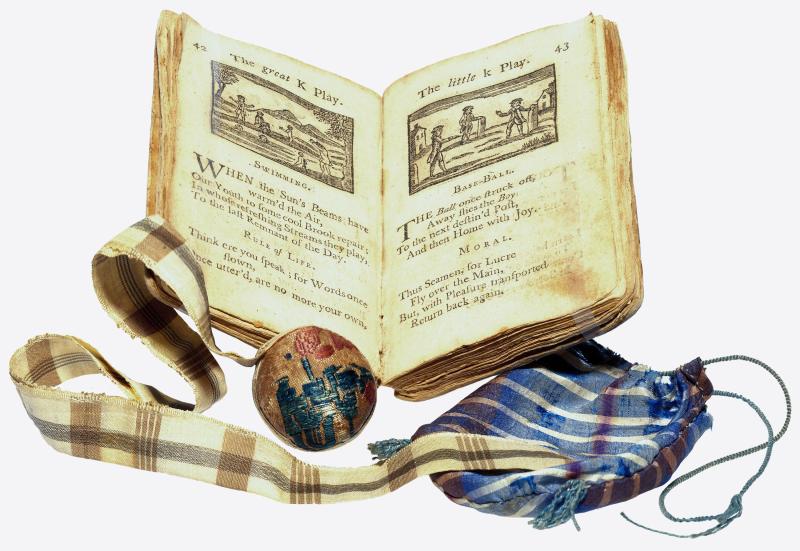

John Newbery's Little Pretty Pocket-Book

The book includes rhymes, letters of the alphabet, fables, depictions of games of the time, and lists of instructions for proper behavior in the presence of adults and other children of different ages. There is a letter of introduction from Jack the Giant Killer, the popular character from numerous English fairy tales.

Several scholars have pointed out the close connection between the Pocket-Book and children's material culture and play activities. It came with a toy that could be used as a "ball" if you were a boy or a "pincushion" if you were a girl. The Morgan Library and Museum in New York City holds what is apparently the only copy of the book complete with ball and pouch. I wonder what kids really did with this toy. Did they use it as intended? Did girls throw it like a ball? Did boys use it as instructed, to track their good behavior, or did they find other uses for it? These material questions remind us that we can think about children's literature not as a set of static texts that children simply receive, but as things with which they interact in various ways, creating new meanings in the act.

Monday, October 15, 2018

Michael Jackson sings "You Can't Win"

Composer-lyricist Charlie Smalls wrote "You Can't Win" for the stage version of The Wiz (1975), but it was dropped after the Baltimore previews. It originally appeared at the beginning of the second act, where it was sung by the slaves of Evilene, the Wicked Witch of the West. It was dusted off for the film version, where it replaced "I Was Born on the Day Before Yesterday" as the Scarecrow's introductory solo. Michael Jackson's performance in this role is considered by many to be the highlight of the film, and this song to be the highlight of his performance. My conversations with fans of the film, particularly in the Black community, suggest that this is one of the most popular songs from The Wiz, along with "Home," and although it goes against the licensing agreement, many school and community theater productions still use this song instead of "I Was Born."

Saturday, October 13, 2018

Bert and Ernie Sing "But I Like You"

"But I Like You" is a song by Jeff Moss sung by Bert and Ernie. It first appeared in 1984 and takes place within a classic Sesame Street scenario--Ernie keeps Bert awake by talking and/or singing. This song belongs to a genre I think of as the Bert and Ernie friendship duet. There are only two or three of them, but they bring to the surface what is tacit in many of the other sketches involving the two friends--the intensity of their relationship, whether you think of them as friends, roommates who are almost like brothers, or even lovers. The Tin Pan Alley style of the song evokes the intimacy of the domestic sphere (indeed they sing to each other in bed) as well as the double entendres (exemplified by Cole Porter) that allow listeners to hear the song on multiple levels.

Friday, October 5, 2018

Repas de bébé

Wednesday, October 3, 2018

Can You Tell Me How to Get to Sesame Street?

The Sesame Street theme song has opened the program since its first episode on November 10, 1969. The lyric, written by Jon Stone and Bruce Hart in collaboration with composer Joe Raposo, describes Sesame Street as a destination ("on my way to where the air is sweet"). Further, it is a destination sought by a speaker without knowledge of its location ("Can you tell me how to get, how to get to Sesame Street?"). The idea of a place "where the air is sweet" seems prompted by the pleasure of a "sunny day." That Sesame Street is kind of a child's paradise is further signaled by references to playing together and friendly neighbors. That it is a magical place filled with the wonders and imagination of the child is made more explicit by the seldom-heard bridge of the song:

It's a magic carpet ride

Every door will open ride

To happy people like you

The opening of doors refers to the inspiration for the name of the show in the expression "Open Sesame," familiar to many kids from the magical story of "Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves."

The world of childhood and the show's educational mission are implied by the music, which uses the most elementary musical relationships in its melody--"sunny day" and "come and play" are set to a falling arpeggiated triad with much of the rest of the musical phrase following scalar patterns. The song is sung by a chorus of children with light, treble voices evoking popular notions of innocent sweetness of childhood.

While Sesame Street itself is, to borrow an expression from Mr. Rogers, a "neighborhood of make-believe," the visuals accompanying the song suggest that kids can find the spirit of Sesame Street in their own neighborhoods and play activities. Kids are shown playing, mostly together but sometimes alone, in urban environments as well as parks and fields that may or may not necessarily be in the city. These images evoke the pastoral as well as the urban--bucolic scenes being especially associated with the Romantic idea of childhood as a thing close to the goodness of nature.

Tuesday, October 2, 2018

Alice's Wonderland: An Early Encounter Between Disney Animation and Its Child

Alice's Wonderland (1923), although it had been produced under Laugh-O-Gram films, was the first film shown to distributors by Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio, which became the Walt Disney Company. In this short, a little girl named Alice pays her first visit to a cartoon studio. The representation of a child as both observer and participant in the making of a cartoon intended for her amusement sets the terms, from this seminal moment, of the cultural work of the Disney empire. Knocking insistently, she finally secures Walt's attention and declares, "I would like to watch you draw some funnies." This statement encapsulates the entire significance of the Disney company, which positioned itself in the marketplace as the safe studio for kids and families, using animation as the medium of choice for demonstrating its child-friendliness and the figure of Walt Disney himself as its imprimatur. Self-reference, to Disney the man, to the studio, and to the technical arts of animation, are on display here, as they often are in animated shorts showing the artist at work and interacting with his creations. This kind of self-reference runs through the Disney corpus, with each film recycling images, tropes, and even specific animated movement sequences from previous films. Walt already is the avuncular figure that he would become to American audiences. The white page on which Walt has been drawing becomes the movie screen as the pictures come to life. Cats play in a band, visually representing in this silent film the important role music would play in future Disney productions. Then, Alice goes home and dreams that she travels to Cartoonland by train, a magical place where a kids' dreams seem to come true and easily seen as an analog to Disneyland. Alice's appearance as a live actor in this cartoon world suggests the immersion of the "real" child in the world of Disney. The dream takes a mild turn for the worse when Alice is chased by lions before waking up (Sorry the very end is missing from this video!). The framing of the adventure as a dream and the name of the protagonist suggest Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865), the kind of fantasy story that, along with fairy tales, would form the backbone of Disney's repertory of animated features starting with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937).

Fairylogue and Radio-Plays

In this picture, L. Frank Baum poses with actors from his Fairylogue and Radio-Plays. Always intent to expand his Oz books into a transmedia franchise, Baum, with this project, created what seems to be a rather unusual media form based on The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), The Marvelous Land of Oz (1904), Ozma of Oz (1907), and one of his non-Oz fantasy books, John Dough and the Cherub.The Fairylogue and Radio-Plays combined hand-colored slide projections and moving film clips with live actors. Baum himself played the narrator in a fashion that sounds reminiscent of popular projection lectures of the nineteenth century, only here he interacted with the movies as well as the live actors. It seems like it was probably as much an advertisement for the books as an attraction in itself. The Fairylogue and Radio-Plays was expensive to produce and to tour. Although it was well-received, it lost money, and the expense sent Baum into bankruptcy. Little more exists of this production than a handful of photographs, a couple of advertisements, and an archived script. None of the slides or films survive, so we'll likely never see those. I am struck by the fact that there are a number of children in the cast, including Romola Remus as Dorothy. I would love to know more about these child actors and how they performed in the show.

Tuesday, September 18, 2018

Mary Poppins Returns

One thing that's missing is a significant sampling of the songs by Marc Shaiman and Scott Wittman, which I of course can't wait to hear.

If the reaction videos can be taken as a measure, the trailer seems to be cuing all the right emotions.

Sunday, September 16, 2018

Pecan Pie Baby

Jacqueline Woodson’s Pecan Pie Baby tells the story of an African American girl, Gia, who is less than happy that she is going to have a new sibling. Aimed at young readers, the book, with illustrations by Sophie Blackall, signals its comforting objective from the outset through its pastel colors and the appealingly round-faced characters. The front cover shows Gia and her Mama in close embrace with Gia’s arm around her mother’s pregnant belly after they have just finished eating pecan pie, the food that Mama uses to comfort Gia and reassure her of her love.

Jacqueline Woodson’s Pecan Pie Baby tells the story of an African American girl, Gia, who is less than happy that she is going to have a new sibling. Aimed at young readers, the book, with illustrations by Sophie Blackall, signals its comforting objective from the outset through its pastel colors and the appealingly round-faced characters. The front cover shows Gia and her Mama in close embrace with Gia’s arm around her mother’s pregnant belly after they have just finished eating pecan pie, the food that Mama uses to comfort Gia and reassure her of her love.Blackall’s illustrations show the relationship between Gia and Mama, using indoor environments, predominantly the home, and Gia's position within them to show her emotional state. The book opens in the fall with Gia and Mama going through Gia’s winter clothes. Instead of throwing them away, however, Mama boxes them up for the new baby. Gia’s room is always shown from a perspective directed toward the far corner, where her bed is situated. In the first two-page spread, the room appears cozy and lived-in, with mother and daughter smiling as they pack up the winter clothes.

This mood is disrupted in the text, however, when Mama brings up what Gia repeatedly refers to in exasperated larger type as the “ding-dang baby.” On the next spread, Gia looks away from her mother (who is always looking at Gia, no matter what) as she tries to talk to her about the coming baby. In such moments of emotional closeness, Blackwell gives us intimate depictions of the characters with few or no details of their surroundings in the background. The passage of time is indicated by the changing of the season from autumn to winter, which is when, according to Mama, the baby will probably arrive (by the first snow). On the first page, trees in cheerful fall colors are framed by the windows in Gia’s room. After the topic of the baby comes up, falling leaves are foregrounded in an exterior view of Gia’s bedroom window as she looks out hoping there won’t be snow. Framed by the window, Gia looks away from Mama as each falling leaf portends the dreaded winter.

This mood is disrupted in the text, however, when Mama brings up what Gia repeatedly refers to in exasperated larger type as the “ding-dang baby.” On the next spread, Gia looks away from her mother (who is always looking at Gia, no matter what) as she tries to talk to her about the coming baby. In such moments of emotional closeness, Blackwell gives us intimate depictions of the characters with few or no details of their surroundings in the background. The passage of time is indicated by the changing of the season from autumn to winter, which is when, according to Mama, the baby will probably arrive (by the first snow). On the first page, trees in cheerful fall colors are framed by the windows in Gia’s room. After the topic of the baby comes up, falling leaves are foregrounded in an exterior view of Gia’s bedroom window as she looks out hoping there won’t be snow. Framed by the window, Gia looks away from Mama as each falling leaf portends the dreaded winter.  Mama remarks that the baby loves pecan pie, and it wants some right now. Gia says the baby is just a copy-cat, because the two of them love pecan pie. This conversation takes place on the same spread dominated by the picture of Gia and Mama in the window with leaves blowing across the pages toward the substantial paragraph of text. There is some space after this text before the single line, “In the kitchen, Mama cut us a big slice.” Then, in the lower right corner of page, there is a tiny picture of the two of them seated side-by-side at the kitchen table, sharing a piece of pecan pie. Their eyes are glancing toward each other, and there is something stylized, possibly even suggestive of folk art, about the way the hold their spoons against their smiling lips. Because of the unusual way in which they eat with their spoons, one is prompted to imagine the taste and texture of the pie, which has an affectionate place in Southern and African American culinary history as a dessert associated with family and holidays. Such a significant moment in the story might well have been its own featured page. The choice to slip it into the corner of a two-page spread suggests that it is the little things—small gestures of love and acts of bonding—that matter. It also allows room for this gesture to grow larger and more significant by the end of the book. In these first few expository pages, the full story has been prefigured on a small scale.

Mama remarks that the baby loves pecan pie, and it wants some right now. Gia says the baby is just a copy-cat, because the two of them love pecan pie. This conversation takes place on the same spread dominated by the picture of Gia and Mama in the window with leaves blowing across the pages toward the substantial paragraph of text. There is some space after this text before the single line, “In the kitchen, Mama cut us a big slice.” Then, in the lower right corner of page, there is a tiny picture of the two of them seated side-by-side at the kitchen table, sharing a piece of pecan pie. Their eyes are glancing toward each other, and there is something stylized, possibly even suggestive of folk art, about the way the hold their spoons against their smiling lips. Because of the unusual way in which they eat with their spoons, one is prompted to imagine the taste and texture of the pie, which has an affectionate place in Southern and African American culinary history as a dessert associated with family and holidays. Such a significant moment in the story might well have been its own featured page. The choice to slip it into the corner of a two-page spread suggests that it is the little things—small gestures of love and acts of bonding—that matter. It also allows room for this gesture to grow larger and more significant by the end of the book. In these first few expository pages, the full story has been prefigured on a small scale.As time passes, leaves keep falling, and “jacket weather” comes. Gia’s fear that the new baby will ruin life as she knows it intensifies. There is a moment of playful abandon when Gia and her friends play “Mama’s Having a Baby.” As the children jump rope to the traditional children’s rhyme, Gia blends into the crowd—it takes the reader a moment to spot her near the end of the line. At this moment, she is able to play through her feelings of resentment (in the rhyme, the baby is sent down the escalator) without being singled out as the girl who’s getting a baby sibling, as happens during an episode in class.

Soon, however, before even arriving, the baby seems to invade Gia's life, world, and physical space. She worries that her friend won't be able to sleep over because the baby will take the extra bed. Her aunties come to visit, but rush through tea and ignore her to talk about the baby, and her uncles invade her room to put the crib together. In a single-page illustration without words, they have strewn furniture parts and tools all over her room, leaving Gia drawn up in fetal position, backed up into the far corner of her room, small and marginalized. At school, the teacher reads a book about a girl who is about to be a big sister, and in contrast to the anonymity she enjoys in the jump-rope scene, she is encircled by her classmates who all look at her.

Soon, however, before even arriving, the baby seems to invade Gia's life, world, and physical space. She worries that her friend won't be able to sleep over because the baby will take the extra bed. Her aunties come to visit, but rush through tea and ignore her to talk about the baby, and her uncles invade her room to put the crib together. In a single-page illustration without words, they have strewn furniture parts and tools all over her room, leaving Gia drawn up in fetal position, backed up into the far corner of her room, small and marginalized. At school, the teacher reads a book about a girl who is about to be a big sister, and in contrast to the anonymity she enjoys in the jump-rope scene, she is encircled by her classmates who all look at her.Gia is sent to her room, where she again sits on her bed in the corner. Her loneliness is deepest here, with the lines where the floor and walls meet converging where she sits in a deep recess of solitude as we look down on her from above. The trees in the window have almost completely shed their leaves.

Judy Garland sings "Over the Rainbow"

Judy Garland is probably best known for her role as Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz (1939) and for her song from the movie, "Over the Rainbow." The song became her signature, and in the 1950s it was a fixture of her concert tours. Typically she sang it right after a recreation of "A Couple of Swells," a clowning song and dance duet which she shared with Fred Astaire in the film Easter Parade (1948). Still in the "tramp" costume from this comedic number, she would sit on the edge of the stage and give a heartfelt rendition of "Over the Rainbow," as though breaking the fourth wall of the preceding comedic performance to bare her soul. In this, the only video of the performance, from her appearance on the Ford Star Jubilee television program of 1955, even as she remains in costume and makeup, the pathos of her real life--the addictions, marital instability, career ups-and-downs, and other struggles of which many of her fans were aware--are foregrounded in a theatrically staged revelation of the person behind the performer.

This revelation of the person behind the performer also plays as a revelation of the child behind the adult. Much has been said about the androgyny of the performance and how Garland's inhabiting the drag of a male tramp intensifies the effect of dislocation--of a person not belonging or not confined by conventional gender and social categories--and the feelings of longing expressed by the song in such conditions of marginalization. Resonances with her gay male and other queer fans is obvious here. Perhaps less obvious, but at least as important, I think, is a kind of age drag. Her tramp character, although an adult, is comically childlike. Indeed, it is an infantalizing portrayal of poverty and, implicitly, race, given its roots in clown stock characters and minstrelsy tropes (which were very much part of Garland's early film career). Whereas in "A Couple of Swells," Garland's tramp is a carefree and child-like adult, in "Over the Rainbow," the character is a window onto the adult's childhood, which persists as the "child inside." Garland's performance channels both the image of the child star's loss of childhood and the impossibility of an adulthood without childlike vulnerability. The poignancy of the performance is, first and foremost, I think, in its queering of the line between child and adult, revealing the latter, in particular, to be a fantasy.

Friday, September 14, 2018

No More Kings!

The "America Rock" episodes of the ABC interstitial cartoon series Schoolhouse Rock presented lessons about American history and democracy that were meant to educate young viewers into citizenship. Schoolhouse Rock used songs in styles of music broadly conceived as rock to help its young viewers remember things like the preamble to the Constitution, adverbs, and multiplication tables. In the case of the nostalgic "America" episodes, a folk-rock sound dominates. The first installment, “No More Kings," opens with an invocation of rock music itself to announce the appearance on the world stage of American democracy:

Rockin' and a rollin', splisin' and a splashin'

Over the horizon, what can it be?

Looks like its going to be a free country.

The song then launches into a narrative of the colonization of the new world describing the proto-USA as a child leaving the nest of mother England.

Oh, they were missing Mother England

They swore their loyalty until the very end

Anything you say, King, it's okay, King

You know, it's kind of scary on your own

Gonna build a new land the way we planned

Can you help us run it till it's grown?

Words, music and image seem designed to tell a story children could relate to. The animation makes the world appear small, so that a ship can easily sail across a small ocean, across which a king can watch his subjects through a spyglass. The Boston Tea Party is represented inside a teacup, which is reminiscent of a child's tea set. The Mayflower and the house, over which people tower, are also toy-like.

The folksy, guitar-based, seventies soft pop style of the music maintains the childlike affect. Most importantly, the pilgrims are described, like children, as dependent on a mother country. They are frightened to be alone in the world, but swearing their loyalty, they want to build a new land according to their own vision. They need help until, like a child, the new nation is “grown.” And they want the king to be proud of them, just as a child seeks a parent’s approval. Both the colonizers and the country they found are thus positioned as innocent by being coded as children.

To maintain the innocence of this narrative, however, requires the erasure of those who would complicate it.

Thursday, September 13, 2018

Pestalozzi and Music Education

Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, the Swiss educator, held that education should be child centered, teaching the student through natural exploration and play. He expressed his view of the education of the whole person by saying that children should learn by "head, hand, and heart." His belief in the proximity of childhood to nature and the natural education of the child was influenced by the philosophy of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, with whom he shared the belief that speech and sound preceded written words ("sound before sign"). Pestalozzi's ideas were influential on American music education through the work of influential music educators like Lowell Mason. Under Pestalozzian principles, children were most naturally and effectively taught music through singing and playful performance rather than reading and writing music. Such ideas were further disseminated in the twentieth century in the music teaching methods developed by Carl Orff and Zoltan Kodaly.

Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, the Swiss educator, held that education should be child centered, teaching the student through natural exploration and play. He expressed his view of the education of the whole person by saying that children should learn by "head, hand, and heart." His belief in the proximity of childhood to nature and the natural education of the child was influenced by the philosophy of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, with whom he shared the belief that speech and sound preceded written words ("sound before sign"). Pestalozzi's ideas were influential on American music education through the work of influential music educators like Lowell Mason. Under Pestalozzian principles, children were most naturally and effectively taught music through singing and playful performance rather than reading and writing music. Such ideas were further disseminated in the twentieth century in the music teaching methods developed by Carl Orff and Zoltan Kodaly.In this video, music educator Jo Ann Champion traces the lineage of Pestalozzian ideas in American music education.

Tuesday, September 11, 2018

Gallimathias Musicum

I've been listening to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's early compositions, and this is one of my favorites. Mozart wrote Gallimathias musicum in 1766, when he was ten years old. It was performed in the Hague for the coming of age of the regent Prince William of Orange the Fifth on his eighteenth birthday, when he was installed as the Stadtholder of the Dutch Republic. Gallimathias seems to mean something like nonsense, gibberish, or a confused state. It's a humorous piece, a quodlibet, which usually indicates a lighthearted composition combining popular tunes in counterpoint. Here, the designation probably refers to the final movement, a fugue on the Dutch tune "Willem van Nassau," which, according to Mozart's father, Leopold, everyone in Holland was "singing, playing, and whistling" at the time.

Saturday, February 25, 2017

Reading and Singing Along to The Wizard of Oz

Tuesday, January 10, 2017

Children of Heaven

When Ali returns from school after the first day of sharing the sneakers, Zahra says she’s embarrassed to wear the shoes because they are dirty. Ali proposes that they wash them. At this point there is a striking shift in the film’s affective register. Twenty minutes into a movie that has relied on everyday realism and made no use of non-diegetic music, even in the opening credits, music is not only heard for the first time, but is foregrounded, directing the viewer’s consciousness to a different relationship with the film’s diegesis. Ali and Zahra scrub the shoes and then begin blowing bubbles, which seem to dance to the music. The delicate, colorful instrumentation conjures connotations of magic, joy, and the sublime (as well as the exotic, to Western ears). No words are exchanged during this moment. The children smile at each other as they blow bubbles, and when they are done, Ali places the shoes on the wall to dry.